Treaty nonresident positions are interesting. Before 2023 we would have said that no tax returns may be due but informational returns are due because of IRS regulations. Now things are uncertain.

In Aroeste v. United States, No. 22-cv-00682, Judge Karen S. Crawford, a U.S. magistrate judge, considered whether Mr. Aroeste’s status under the treaty has any effect on the FBAR filing requirement. The government argued that Mr. Aroeste’s status under the treaty is irrelevant because the treaty solely concerns residence for income tax purposes under title 26 of the U.S. Code, whereas FBAR penalties are assessed under title 31. The government’s problem with this argument was that FinCEN had chosen to define residence by explicit reference to title 26 and its regulations. The judge had no difficulty tracing the definitions:

A non-U.S. citizen is treated as a “resident alien” if he or she is a “lawful permanent resident of the United States at any time” during an applicable calendar year. 26 U.S.C. section 7701(b)(1)(A)(i). An individual is a “lawful permanent resident” if he or she has been “lawfully accorded the privilege of residing permanently in the United States as an immigrant in accordance with immigration laws” and if “such status has not been revoked (and has not been administratively or judicially determined to have been abandoned).” Id. section 7701(b)(6). However, “lawful permanent resident” status ceases to exist — at least for tax purposes — if an individual “commences to be treated as a resident of a foreign country under the provisions of a tax treaty between the United States and the foreign country, does not waive the benefits of such treaty applicable to residents of the foreign country, and notifies the Secretary of the commencement of such treatment.” Id.

The court rejected the government’s argument that it “does not matter” how Mr. Aroeste was treated under the treaty because “it only matters that Mr. Aroeste has lawful permanent residence and has not rescinded that residency.” The court pointed out that the statutory framework explicitly provides that “lawful permanent resident” status can be abrogated, for tax purposes only, by application of the treaty, without requiring individuals to forsake their immigration status to claim the taxation benefits of a tax treaty.

In summary, on November 21, 2023, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California in United States v. Aroeste, No. 22-cv-00682, denied the government’s motion for summary judgment and granted, in part, the taxpayer’s motion for summary judgment.

- This decision is a major victory for those dual residents who rely on treaty tie-breaker provisions to demonstrate that such persons are not subject to FBAR filing requirements and this, indeed, as the federal magistrate ruled earlier in the year constitutes an “escape hatch” from these filing obligations.

- In the end, the taxpayer’s argument that he did not have U.S. residency status because of his Mexican residency as determined under the treaty tie-breaker test meant that he was not a United States person for FBAR filing purposes.

- The government’s argument that the taxpayer did indeed constitute a United States person because he did not assert his treaty tie-breaker position until the IRS examination began, did not serve as the ace in the hole to the government’s motion for summary judgment.

- In weighing the government’s and taxpayer’s arguments, the court held that submission of the untimely notice of his treaty tie-breaker position did not constitute a waiver of treaty benefits when filed not with the original returns but on amended returns. The court explained that Section 6712 provides the consequences for this filing error.

- In weighing the government’s and taxpayer’s arguments, the court held that submission of the untimely notice of his treaty tie-breaker position did not constitute a waiver of treaty benefits when filed not with the original returns but on amended returns. The court explained that Section 6712 provides the consequences for this filing error.

Now this case is being appealed as of January 2024 but for taxpayers who do take such a treaty position and it is subsequently challenged by the IRS? In your reasonable cause statement this ruling can perhaps be helpful.

What happens when a foreign individual who is neither a U.S. citizen nor a green card holder on U.S. income tax laws?

We need to determine the person’s residence for income tax purposes. But what is to be done when the individual is resident in multiple jurisdictions? For this purpose, U.S. domestic law, foreign law, and residency rules under any applicable income tax treaty must be looked at.

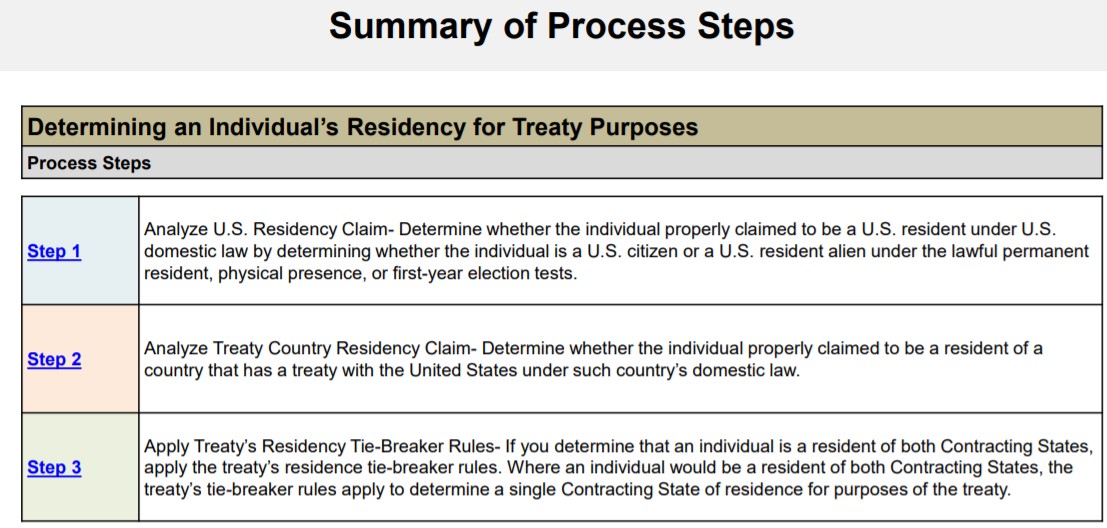

The Practice Unit “Determining an Individual’s Residency for Treaty Purposes” was published on July 3, 2018.

It provides guidance on how to determine tax residency under an applicable U.S. income tax treaty.

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/tre_p_016_02_01_06.pdf

Treaties generally have a provision for determining residency in the case of dual residency in both the U.S. and the treaty partner country. These rules are often referred to as the Tie-Breaker Rules.

The Practice Unit summarizes the steps for applying the Tie-Breaker Rules as follows:

- Determine whether the individual properly claimed to be a U.S. resident under domestic U.S. tax law.

- Determine whether the individual properly claimed to be a resident of a treaty partner.

- Apply the treaty Tie-Breaker Rules in a case of dual residency.

The Practice Unit uses Article 4, the Residency Article, of the 2006 U.S. Model Income Tax Convention (“2006 U.S. Model Treaty”)1 for illustration purposes and explicitly advises that every treaty is different and will thus have to be analyzed separately. Further, it advises to carefully review any additions or governmental comments on a treaty.2

STEP 1 – U.S. RESIDENCY CLAIM

The Practice Unit starts by reminding that, under U.S. domestic law, a person is a U.S. resident if such person

(i) is a U.S. citizen,

(ii) is a U.S. green card holder,

(iii) is a U.S. resident under the Substantial Presence Test,3 or

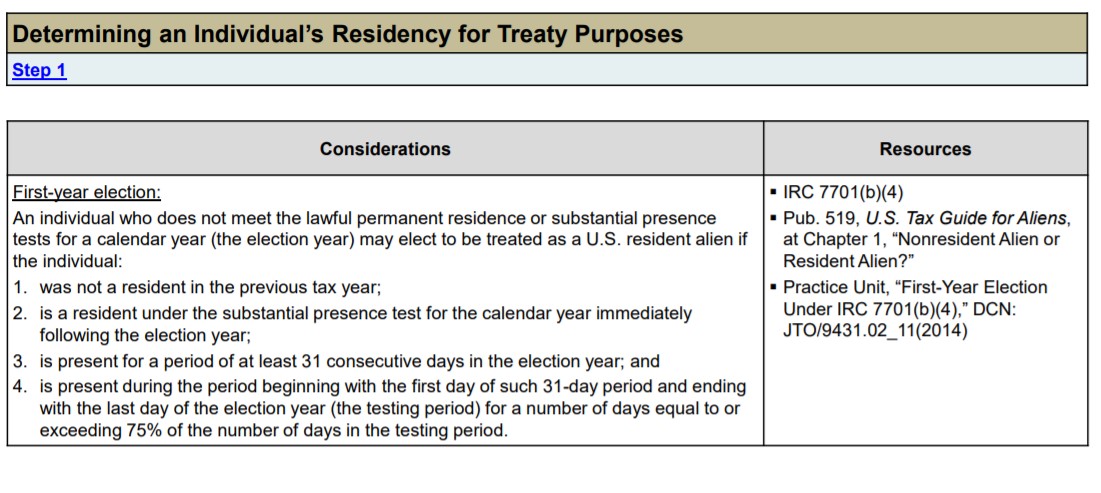

(iv) makes a first-year election to be treated as a U.S.-resident individual.

In addition to Code §7701(b)(1), which contains the definitions of resident and nonresident aliens, the Practice Unit surprisingly quotes Lujan v. Comm’r.4 and I.R.S. Info. Letter 2013-00215 instead of simply referencing the Treasury Regulations under §7701(b)(1).

- In Lujan v. Comm’r., the Tax Court dealt with the Substantial Presence Test and concluded, in relevant part, that the taxpayer incorrectly failed to include the date of exit from the U.S. and the date of entry into the U.S. for purposes of the test.

- I.R.S. Info. Letter 2013-0021 examines the residency rules of the U.S.-German Income Tax Treaty. (That treaty’s Residency Article is the same as Article 4 the 2006 U.S. Model Treaty.) The letter then turns to Code §7701(b)(1) and the regulations thereunder to determine U.S. residency. The letter constitutes a comprehensive tool for I.R.S. agents applying the Substantial Presence Test. It (i) lays out the general definition of U.S. residents, (ii) looks at the general Substantial Presence Test rules, (iii) explains the Closer Connection Test exception, (iv) cites the rules that disregard certain days of presence under the Substantial Presence Test because the individual is either an “exempt individual” or continues to stay in the U.S. because of a medical condition preventing him or her from leaving, and (v) looks at the first-year election.

I.R.S. agents are instructed to look for U.S. residency indicia by proceeding as follows:

- When an individual files a Form 1040 NR, U.S. Nonresident Alien Income Tax Return, the Practice Unit points out that a closer look at items B to H of Schedule OI (Other Information) can help I.R.S. agents determine U.S. residency.

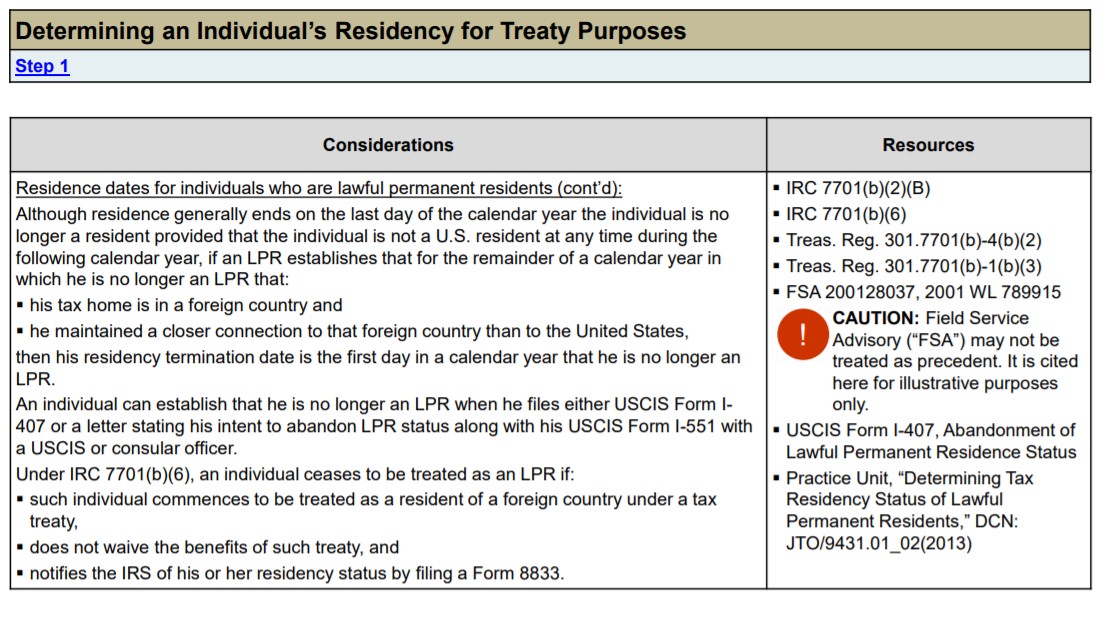

- Agents are also instructed to look for Form I-551, Alien Registration Receipt Card, also known as the green card. The Practice Unit provides residency starting date and ending date guidelines for green card holders and for Substantial Presence Test purposes. For green card holders, I.R.S. agents are reminded that green card status is ended

- by filing either (i) U.S.C.I.S. Form I-407 or (ii) a letter stating the taxpayer’s intent to abandon his or her green card along with U.S.C.I.S. Form I-551 with a U.S.C.I.S. or consular officer, or

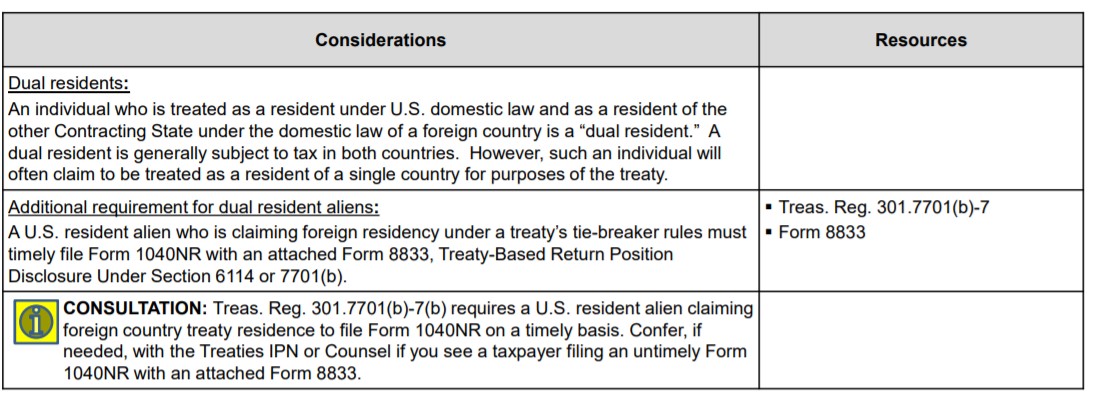

- pursuant to Code §7701(b)(6), if the taxpayer (i) starts to be treated as a resident of a country other than the U.S. under a tax treaty, (ii) does not waive treaty benefits, and (iii) notifies the I.R.S. of his or her residency status by filing a Form 8833, Treaty-Based Return Position Disclosure Under Section 6114 or 7701(b).

With respect to the latter, notably, taxpayers should be careful about filing a treaty return position claiming non-U.S. residency when they hold a green card, since this could trigger an exit tax exposure. Towards the end of the Practice Unit, this potential exit tax exposure is explicitly pointed out.

For treaty purposes, the Practice Unit states that, pursuant to Article 4 of the 2006 U.S. Model Treaty and the Treasury explanations thereunder, a U.S.-resident individual is defined the same way as under U.S. domestic law with one exception: A non-U.S. person married to a U.S. citizen or U.S. resident can elect to be treated as a U.S. resident for income tax purposes. Such an election disqualifies the individual from claiming the benefit of the Tie-Breaker Rules.6

Finally, the Practice Unit cautions that certain treaties require additional tests to be met in order for a U.S. citizen or green card holder to be considered as a U.S. resident. For example, the

individual may be required to

- have a substantial presence, permanent home, or habitual abode in the U.S. and not be treated as a resident of a third country under a treaty between the other contracting state and that third country, or

- have a substantial presence in the U.S. or be a resident of the U.S. and not a resident of the third country under the Tie-Breaker Rules. The Practice Unit cites the U.S.-U.K. and U.S.-France treaties as examples in this context.

The Practice Unit concludes that for purposes of Step 1, the agent must determine whether the individual is a U.S. resident both under U.S. domestic law and under the treaty.

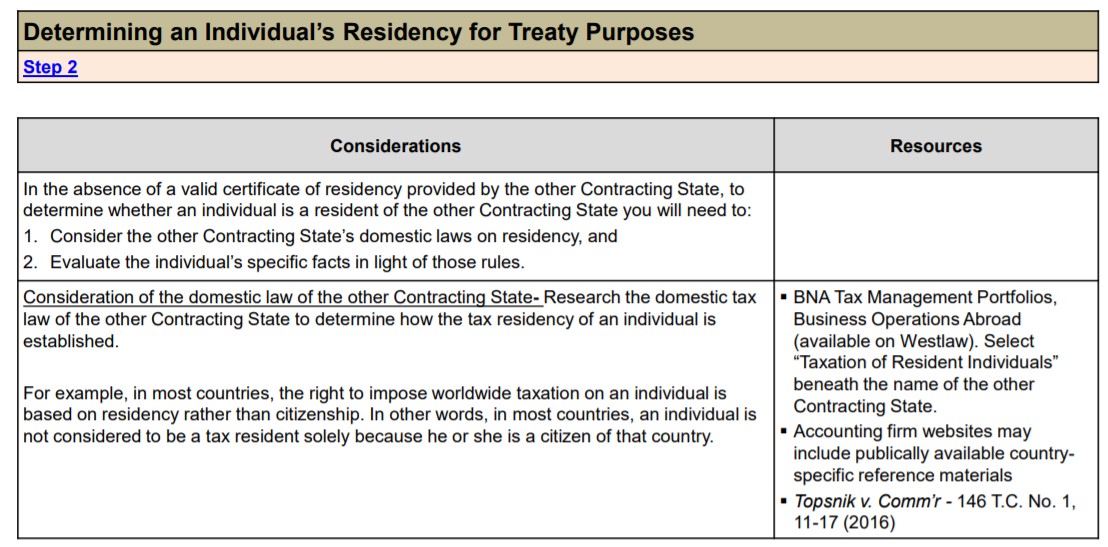

STEP 2 – TREATY COUNTRY RESIDENCY CLAIM

In order to determine whether an individual properly claimed residence in a treaty country, the Practice Unit advises that I.R.S. agents should look for the following:

- Information on tax returns, e.g., responses on Schedule OI of Form 1040NR

- Responses on Form 9210, Alien Status Questionnaire

- The exchange of information provisions available under the treaty, or tax information exchange agreements, that can be used to receive information from outside the U.S.

- A foreign equivalent to a certificate of residency7

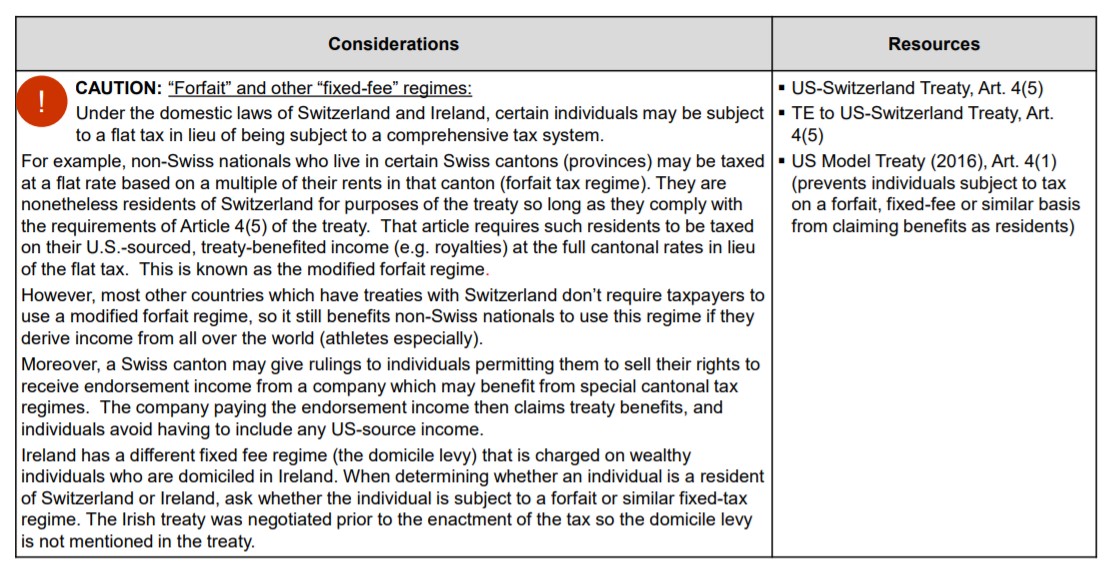

- The presence of a “forfait” or another fixed-fee regime8

STEP 3 – TREATY TIE-BREAKER RULES

I.R.S. agents move to Step 3 if they determine that the individual is a resident of the other country for treaty purposes and also a resident of the U.S. If not, the agents are asked to skip Step 3 and go to the section entitled “Other Considerations or Impact to Audit.”

The Tie-Breaker Rules are used to determine a single country of residence in a case of dual residency. Citing the 2006 U.S.

Model Treaty, the Practice Unit provides that the Tie-Breaker Rules generally look at the following factors:

- The existence and location of a permanent home

- The center of vital interests

- The individual’s habitual abode

- Nationality

The Tie-Breaker Rules test these factors in the stated order. Once an element has been satisfied with respect to the U.S. or the treaty country, residency is attributed accordingly. If the test is met for both countries, the next factor is tested.

The I.R.S. cautions that not all treaties have Tie-Breaker Rules and cites the U.S.-China and the U.S.-Pakistan treaties as examples. While not stated in the Practice Unit, residency would, in these cases, be determined under a competent authority procedure (i.e., in consultations between the competent authorities of the two countries in issue).10

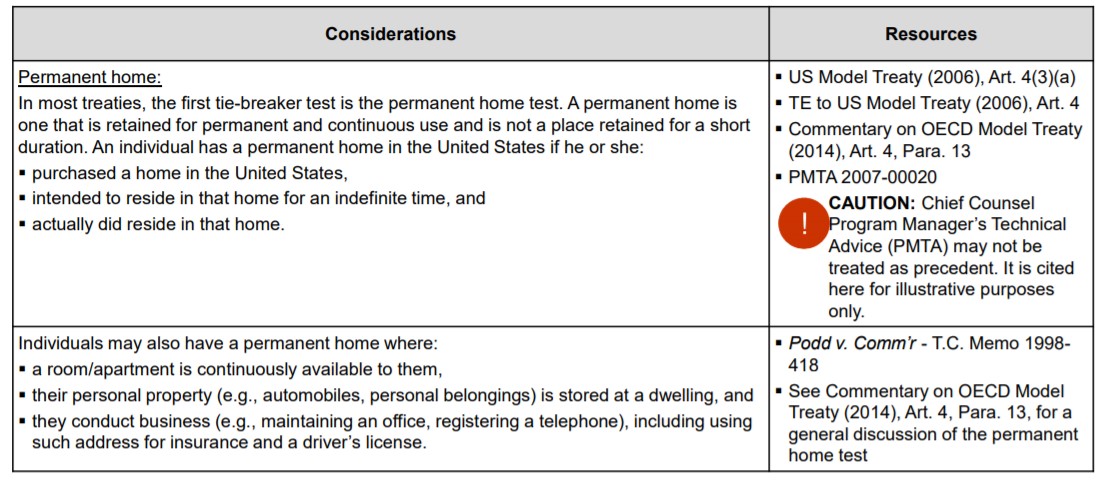

Permanent Home

Under the Tie-Breaker Rules, an individual has a permanent home in the U.S. if

· the individual (i) purchased a home in the U.S., (ii) intended to reside in that home for an indefinite time, and (iii) actually did reside in that home; or

· the individual (i) has a room or apartment continuously available, (ii) stores personal property (e.g., automobiles or personal belongings) at the dwelling, and (iii) conducts business (e.g., maintaining an office, registering a telephone), including using the address for insurance and a driver’s license.

Certain treaties look at an individual’s family life to determine a permanent home. The Practice Unit cites the U.S.-Australia, U.S.-Indonesia, and U.S.-Korea treaties.

If the individual has only one permanent home, the application of the Tie-Breaker Rules ends there. If the individual has a permanent home in both treaty countries, the individual’s center of vital interests must be determined.

Center of Vital Interests

To determine an individual’s center of vital interests, one must look at their personal, community, and economic relations.

The following factors are not exclusive. Rather, all facts and circumstances are relevant and must be evaluated in their entirety.

· An individual’s personal relations can be identified (i) by such individual’s family location, including parents and siblings, and where the individual spent his or her childhood, or (ii) in the case of a person’s recent relocation, by whether the family moved from their permanent home to join the individual or the individual located to a second state. However, certain treaties, like the U.S.-Israel treaty, have a different definition of the center of vital interests.

· An individual’s community relations are determined by the location of the individual’s (i) health insurance, (ii) medical and dental professionals, (iii) driver’s license or motor vehicle registration, (iv) health club membership, (v) political and cultural activities, and (vi) ownership of bank accounts.

· A person’s economic relations are identified by where the individual (i) keeps his or her investments or conducts business, (ii) incorporated a business, and (iii) retains professional advisors (e.g., attorneys, agents, and accountants).

Habitual Abode

An individual’s habitual abode is the place where the individual has a greater presence during the calendar year.

Nationality

An individual’s nationality is determined by their citizenship or state of nationality. An individual is unlikely to be a U.S. national if they are not a U.S. citizen.

To determine the individual’s state of nationality, agents should look to passports and/or U.S.C.I.S. Forms I-94, and reconcile these documents with the individual’s Form 1040NR, Schedule OI, Item A, which inquires about the filer’s citizenship. An exchange of information request may also be submitted.

BEYOND STEP 3

If, after applying these tests, the individual still has dual residency, the competent authorities will try to assign a residency country by means of mutual agreement.

Footnotes

1 The most recent version of the U.S. Model Income Tax Convention was released on February 17, 2016. However, as of this publication, no technical explanation of the treaty have been published.

2 The I.R.S. expressly refers to treaty protocols, memoranda of understanding or exchanges of notes, technical explanations from the Treasury Department, Joint Committee on Taxation reports on a treaty, Senate Foreign Relations Committee report on a treaty, relevant case law, competent authority agreements, and guidance issued by the I.R.S.

6 Treas. Reg. §1.6013-6(a)(2)(v).

7 In this respect, the I.R.S. cautions that the certificate can only be relied on if a reasonably prudent person would not doubt the certificate. Absent such a certificate, the Practice Unit requires agents to (i) consider the other country’s domestic laws of residency and (ii) evaluate the individual’s specific facts in light of those rules. It recommends using the BNA Tax Management Portfolios and the information found on the websites of accounting firms.

8 Here, the I.R.S. gives Switzerland and Ireland as examples.

9 Note that a similar test exists under U.S. domestic law as an exception to the- Substantial Presence Test (Treas. Reg. §§301-7701(b)-2(a)(1)). If the taxpayer can substantiate closer connections to a single foreign country in line with the rules of the domestic Closer Connection Test, residency will be assigned to the foreign country. This test does not apply if the taxpayer has been in the U.S. for 183 days or more in the current year.

10 Cf. U.S.-China Income Tax Treaty, art. 4(2) for dual resident individuals and art. 4(3) for dual resident corporations.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

Source www.mondaq.com

U.S. Residency Certification Income Tax Treaty

Many foreign countries withhold tax on certain types of income paid from sources within those countries to residents of other countries. The rate of withholding is set by that country’s internal law. An income tax treaty between the United States and a foreign country often reduces the withholding rates (sometimes to zero) for certain types of income paid to residents of the United States. This reduced rate is referred to as the treaty-reduced rate. Many U.S. treaty partners require the IRS to certify that the person claiming treaty benefits is a resident of the United States for federal tax purposes. The IRS provides this residency certification on Form 6166, a letter of U.S. residency certification. Form 6166 is a computer-generated letter printed on stationery bearing the U.S. Department of Treasury letterhead, which includes the facsimile signature of the Field Director, Philadelphia Accounts Management Center.

Form 6166 will only certify that, for the certification year (the period for which certification is requested), you were a resident of the United States for purposes of U.S. taxation or, in the case of a fiscally transparent entity, that the entity, when required, filed an information return and its partners/ members/owners/beneficiaries filed income tax returns as residents of the United States. Upon receiving Form 6166 from the IRS, unless otherwise directed, you should send Form 6166 to the foreign withholding agent or other appropriate person in the foreign country to claim treaty benefits. Some foreign countries will withhold at the treaty-reduced rate at the time of payment, and other foreign countries will initially withhold tax at their statutory rate and will refund the amount that is more than the treaty-reduced rate on receiving proof of U.S. residency. Other conditions for claiming treaty benefits. In order to claim a benefit under a tax treaty, there are other requirements in addition to residence. These include the requirement that the person claiming a treaty-reduced rate of withholding be the beneficial owner of the item of income and meet the limitation on benefits article of the treaty, if applicable.

The IRS cannot certify whether you are the beneficial owner of an item of income or that you meet the limitation on benefits article, if any, in the treaty. You may, however, be required by a foreign withholding agent to establish directly with the agent that these requirements have been met. You should examine the specific income tax treaty to determine if any tax credit, tax exemption, reduced rate of tax, or other treaty benefit or safeguards apply. Income tax treaties are available at IRS.gov/businesses/internationalbusinesses/united-states-income-taxtreaties-a-to-z.

Value Added Tax (VAT)

Form 6166 can also be used as proof of U.S. tax residency status for purposes of obtaining an exemption from a VAT imposed by a foreign country. In connection with a VAT request, the United States can certify only to certain matters in relation to your U.S. federal income tax status, and not that you meet any other requirements for a VAT exemption in a foreign country. General Instructions Purpose of Form Form 8802 is used to request Form 6166, a letter of U.S. residency certification for purposes of claiming benefits under an income tax treaty or VAT exemption. You cannot use Form 6166 to substantiate that U.S. taxes were paid for purposes of claiming a foreign tax credit. You cannot claim a foreign tax credit to reduce your U.S. tax liability with respect to foreign taxes that have been reduced or eliminated by reason of a treaty. If you receive a refund of foreign taxes paid with the benefit of Form 6166, you may need to file an amended return with the IRS to adjust any foreign tax credits previously claimed for those taxes. When To File You should mail your application, including full payment of the user fee, at least 45 days before the date you need whether that account holder is an individual or a nonindividual applicant. to submit Form 6166. We will contact you after 30 days if there will be a delay in processing your application. You can call (267) 941-1000 (not a toll-free number) and select the U.S. residency option if you have questions regarding your application. Early submission for a current year certification. The IRS cannot accept an early submission for a current year Form 6166 that has a postmark date before December 1 of the prior year. Requests received with a postmark date earlier than December 1 will be returned to the sender. For example, a Form 6166 request for 2021: • Received with a postmark date before December 1, 2020, cannot be processed; • Received with a postmark date on or after December 1, 2020, can be processed with the appropriate documentation.

Who Is Not Eligible for Form 6166

In general, you are not eligible for Form 6166 if, for the tax period for which your Form 6166 is based, any of the following applies.

• You did not file a required U.S. return.

• You filed a return as a nonresident (including Form 1040-NR, Form 1040-NR-EZ (before tax year 2020), Form 1120-F, Form 1120-FSC, or any of the U.S. possession tax forms).

• You are a dual resident individual who has made (or intends to make), pursuant to the tie-breaker provision within an applicable treaty, a determination that you are not a resident of the United States and are a resident of the other treaty country. For more information and examples, see Regulations section 301.7701(b)-7.

• You are a fiscally transparent entity organized in the United States (that is, a domestic partnership, domestic grantor trust, or domestic LLC disregarded as an entity separate from its owner) and you do not have any U.S. partners, beneficiaries, or owners.

• The entity requesting certification is an exempt organization that is not organized in the United States.

• The entity requesting certification is a trust that is part of an employee benefit plan during the employee benefit plan’s first year of existence, and it is not administered by a qualified custodian bank, as defined in 17 CFR 275.206(4)-2(d)(6)(i).

Individuals With Residency Outside the United States

If you are in any of the following categories for the current or prior tax year for which you request certification, you must submit a statement and documentation, as described below, with Form 8802.

1. You are a resident under the internal law of both the United States and the treaty country for which you are requesting certification (you are a dual resident).

2. You are a lawful permanent resident (green card holder) of the United States or U.S. citizen who filed Form 2555.

3. You are a bona fide resident of a U.S. possession.

If you are a dual resident described in category 1, above, your request may be denied unless you submit evidence to establish that you are a resident of the United States under the tie-breaker provision in the residence article of the treaty with the country for which you are requesting certification. If you are described in category 2 or 3, attach a statement and documentation to establish why you believe you should be entitled to certification as a resident of the United States for purposes of the relevant treaty. Under many U.S. treaties, U.S. citizens or green card holders who do not have a substantial presence, permanent home, or habitual abode in the United States during the tax year are not entitled to treaty benefits. U.S. citizens or green card holders who reside outside the United States must examine the specific treaty to determine if they are eligible for treaty benefits and U.S. residency certification. See Exceptions, later. If you are described in category 2 and are claiming treaty benefits under a provision applicable to payments received in consideration of teaching or research activities, see Table 2 for the penalties of perjury statement you must either enter on line 10 of Form 8802 or attach to the form.

Exceptions

You do not need to attach the additional statement or documentation requested if you:

• Are a U.S. citizen or green card holder; and

• Are requesting certification only for Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Hungary, Iceland, India, Kazakhstan, Malta, New Zealand, Russia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, or Ukraine; and The country for which you are requesting certification and your country of residence are not the same.

• Form 1116, Foreign Tax Credit If you have filed or intend to file a Form 1116 claiming either a foreign tax credit amount in excess of $5,000 U.S. or a foreign tax credit for any amount of foreign earned income for the tax period for which certification is requested, you must submit evidence that you were (or will be if the request relates to a current year) a resident of the United States and that the foreign taxes paid were not imposed because you were a resident of the foreign country. In addition, individuals who have already filed their federal income tax return must submit a copy of it, including any information return(s) relating to income, such as Form W-2 or Form 1099, along with the Form 1116. Your request for U.S. residency certification may be denied if you do not submit the additional materials.

United Kingdom

If you are applying for relief at source from United Kingdom (U.K.) income tax or filing a claim for repayment of U.K. income tax, you may need to complete a U.K. certification form (US-Individual 2002 or US-Company) in addition to Form 8802. For copies of these forms, contact HM Revenue and Customs. On the Internet at HMRC.gov.uk, enter “US Double Taxation” in the search box, and scroll down to the link for the Form US-Individual 2002 or Form US-Company. Call 44-135-535-9022 if calling from outside the U.K., or 0300-200-3300 if calling from the U.K. Send the completed U.K. form to the IRS with your completed Form 8802.

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i8802.pdf